By Steve Wilent

The Woodsman’s Take, July 24, 2024

A July 23 front-page story in The Oregonian recently declared that this is “another monster fire year” in the Pacific Northwest. The next day, the Associated Press published an article entitled “Wildfire smoke chokes parts of Canada and western US, with some areas under air quality alerts.”

This may turn out to be a monster fire year. As of this writing the number of acres burned (more than 3.6 million) is just a bit higher than the 10-year average to date (3.25 million acres), according to the National Interagency Fire Center. Some fire years are worse than others. Last year’s total of 2.7 million acres burned nationwide was “merely” one-quarter of the more than 10 million acres burned in each of 2017 and 2020.

Ten million acres is a bit larger than the total area of Vermont and Massachusetts combined.

Here’s an even larger number: 73 million. That’s the number of acres of National Forest land “at risk from wildland fires that could compromise human safety and ecosystem integrity.” So said US Forest Service Chief Dale Bosworth in a speech given more than 20 years ago. More recent estimates are that 63 to 80 million acres are at risk from wildfires.

Note that 73 million acres is a bit larger than the entire state of Arizona. And Bosworth’s figure doesn’t include the millions of acres managed or owned by other organizations and individuals.

Our wildfire problem, which is primarily in the Western US, isn’t small and it isn’t new.

“The problem didn’t develop in the last 10 to 15 years,” said Chief Bosworth in his 2002 speech. “It took generations to develop. For most of the last century, we focused on removing big trees and suppressing all fires. In the process, we altered the land.”

Bosworth meant that we humans altered our forests. Can we alter them again, manage them, to reduce the risk of large destructive wildfires and leave forests that are healthier and more resilient?

Yes. We need to do something, since not only are millions of acres at risk, but so are millions of homes, businesses, and human lives. Numerous government agencies, private landowners, and others are taking action. Earlier this year, Randy Moore, Chief of the US Forest Service, told Congress that his agency aims to treat 4 million acres in the coming year, if funding is available—a small fraction of the 193 million acres the agency manages.

Despite such efforts, the risk of wildfire is increasing as fuels accumulate in our forests and temperatures rise. The average annual temperature in the western US has increased more than 2 degrees Fahrenheit over the last century, and the trend isn’t likely to change in the short to medium term.

And although there is virtually no up or down trend in precipitation over the last century, many areas in our mountains are getting more rain and less snow than they used to, and what snow does fall melts earlier in the spring, leaving large areas drier and lengthening the wildfire season. This trend isn’t likely to change in the short to medium term, either.

What can we do? Aside from curtailing the number of fires started by people—humans cause around 85 percent of wildfires in the US each year—we can remove some of the small- and medium-size trees, brush, and debris that fuel wildfires. Science-based forest management is needed: thinning overcrowded forests and removing small logs and other unmerchantable material by carefully burning it with low-intensity prescribed fires, piling it and burning it, or even hauling it away to use as fuel for generating electricity. Doing so not only reduces the risk of large, intense wildfires, but also helps the remaining large trees survive in a warmer climate.

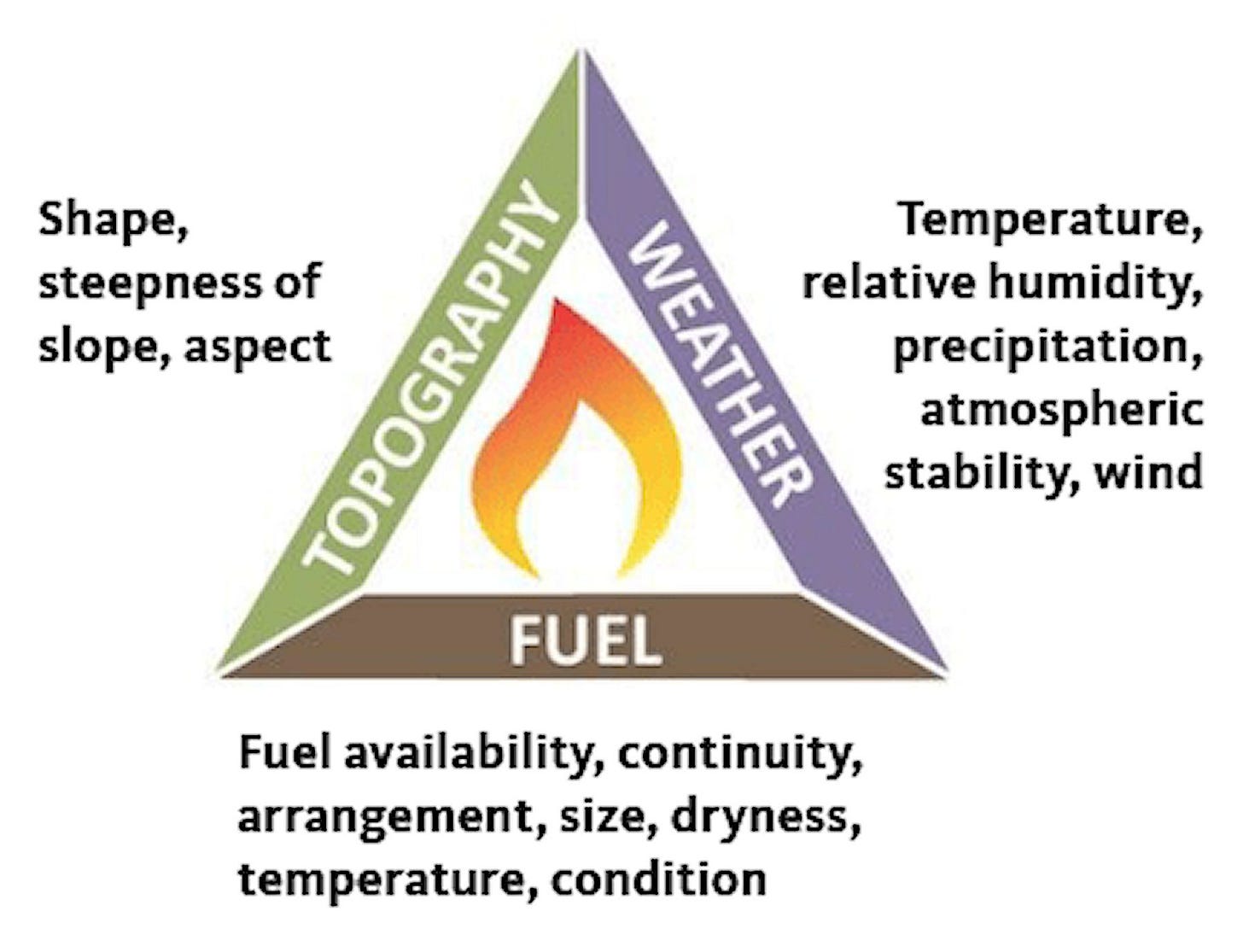

Here’s another way to look at it. The sides of the “wildland fire triangle” represent the three main factors in how wildfires burn: fuels, weather, and topography (the shape of the land). We can’t change the weather or topography, but we can change the amount and arrangement of fuels.

With less fuel to burn, wildfires will be less intense and firefighters will have better chances of controlling them.

To some people, thinning and fuels reduction is more harmful than beneficial. They say thinning allows more sunlight to reach the forest floor, drying fuels on the ground and making them more flammable, and that winds can more easily penetrate more-open stands and thus can increase a fire’s rate of spread. This may be true in some cases. However, as a forester and former wildland firefighter, I can tell you that with less fuel to burn and more space between the trees, fires will be less intense and devastating crown fires much less likely.

Imaging putting a handful of dry twigs into an otherwise empty fire ring in your back yard. Once lit, the twigs will burn for a minute or two and then go out, producing little heat, flame, and smoke. Start again with twigs and then pile of a few pieces of kindling and a small log or two, and you have the beginnings of a cozy campfire.

Try building a fire with, say, several hundred pounds of dry kindling and logs, and you have the makings of a large, hot fire. Make such a fire on a dry, windy summer day, and it may spread to the woods—and then maybe your house, too, if an ember falls into a gutter clogged with dry pine needles. Or a gutter on your neighbor’s house. This illustrates the fuel situation in many forests in the western US and Canada. Reducing the risks of large, destructive wildfires requires reducing the amount of fuel available to burn.

There’s much more to the science of fire behavior and the forest management practices that influence the way wildfires burn. Have a question about forest management and wildfire? Let me know. Email: SWilent@gmail.com.

Steve Wilent is an independent forester, educator, and journalist who lives in Zigzag, Oregon. Contact him at SWilent@gmail.com.

Please reprint, republish, and pass along this essay. No charge! This and all essays and articles on The Woodsman’s Take are covered by a Creative Commons license. Need a shorter version? Photos? Find a typo or other error? Let me know. Email: SWilent@gmail.com.

Hi Steve,

Thanks for a writing a great common sense article for public consumption. We need the voice of reason in this critical time to manage our forests.